Dissociation: Guardian or Prison Guard?

Sometimes I have no idea how I feel. Understanding, naming and sitting with my emotions does not come naturally to me; I am most comfortable in my head, trying to overthink (and sometimes magical think) my way out of feeling bad.

And when reality is especially distressing, I have a part of me that locks everything down and goes under like a stealth submarine. The world becomes a cramped, muffled place; nothing can touch me. I can subsist on fantasies, day dreams, stories and never have to deal with the realities in front of me. I can get lost in the byzantine maze of my own inner thought processes.

I’ve worked hard to be more in tune with myself, sit with my own inner states with patience and compassion. And yet, this week has reminded me how much I’m still a fellow traveler stumbling my way on the path of self-awareness. I try to practice what I preach yet many times fail miserably.

Dissociation as Guardian

I’m not alone in having a protector part that feels the antidote to overwhelm is system shut down. I see it in sessions sometimes: we’ll be talking about a particularly challenging event/emotion/situation and all of a sudden, the client has totally checked out. Sometimes the dissociation is like narcolepsy— they get suddenly very tired and can hardly think (I have this response in my own therapy sometimes as well). Sometimes they simply freeze, staring at me like a deer in the headlights. Either way, they’re no longer fully present.

Dissociation can be a useful strategy in times of extreme stress or trauma. It takes us away from having to feel everything so we can still function. It boxes up all those overwhelming feelings and disconnects us from the harsh reality so that we can respond to the crisis at hand. In the case of abuse or major physical trauma like a car accident, it disconnects us from what is happening to our body so that we don’t have to feel so much pain.

I remember the first time my dissociative part came online— I had just turned eight years old. I was pulled out of class to be told by my mom that my father was dead. I can remember the feeling, as if someone took a tennis racket to a part of me and lobbed her like a furry green ball into the dark recesses of my heart. That part of me stayed exiled for a very long time, guarded fiercely by dissociation. Shutting down that part of me allowed me to keep moving forward: to go to school, to play with my friends, to watch out for my sisters and hyper-monitor my very sad mother—in short, to seem normal at a time when my whole world was upside down. However, it also kept me from knowing my own heart, which had its own repercussions as I became an adult.

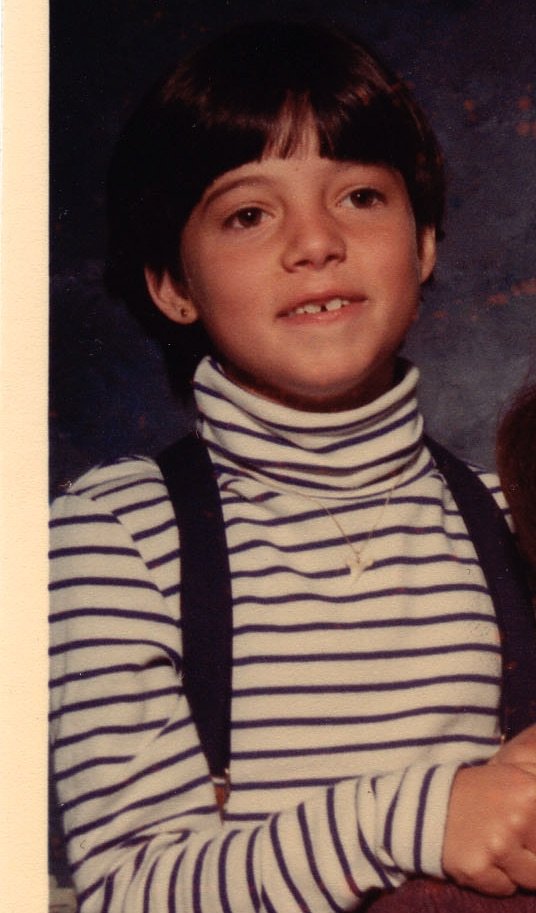

This is me at around the age of 8 or 9 right after my dad died. Outfit and bowl cut I shamelessly blame on my mother…My god, look at those teeth! Thank you modern dentistry.

This week, with the death of a dear friend, I became re-acquainted with my dear pal Dissociation. It shows up whenever a death occurs which unfortunately has been all too often in the last few years. I am grateful for it. I know it’s trying to protect me from being overwhelmed by the enormity of having to contemplate the non-existence of people I love, of trying to fathom a world without certain people in it. It allows me to function day to day, to show up in sessions for others and not be overwhelmed by my own feelings.

For me dissociation comes in as a blank heaviness, like I’m moving through molasses. I look super calm and can get things done, but I’m not feeling anything. It can also look like all of the following:

· Brain fog and trouble thinking

· Wanting to go to sleep in the middle of a challenging situation

· Feeling disconnected from reality and/or one’s body

· Not able to identify what you’re feeling

· Somatic symptoms like your heart is racing or you’re feeling light-headed

· Frozen in place, flashbacks, losing track of time, spending more time in the fantasy world inside your head instead of engaging with the real world

It just occurred to me now as I was listing the above symptoms, how much of my childhood I spent in dissociation. After my dad died, I had trouble concentrating. I was always being called out by the teacher for “daydreaming”—so much so my mom threatened to cancel a trip to Disneyland if I didn’t get my act together. Up until this very moment, I had always chalked this up to being a bit of a space case, and not the fact that my dad had just died and I had no idea how to be in reality anymore.

Check-In

Have you ever experienced dissociation? If so what was happening? How did it feel for you?

Can you tell when one of your loved ones is dissociating? Perhaps you can tell when they “zone out” when you’re talking?

Dissociation as Prison Guard

While dissociation is protective in the short-term, in the long-term it becomes our jailer. When we disconnect, we don’t just disconnect from “bad” feelings, but from joy, laughter, love—everything that brings people together. It means we don’t have access to some of our most important parts of ourselves, the parts that carry vital sources of data on who we are and what we need. We mistake numbness for calmness, lack of access to heart for lack of heart. We begin to think of ourselves at best as “good in a crisis” and at worst as callous and uncaring. For me, I secretly thought there was a piece missing in me, a piece that would allow me to feel everything everybody else did.

While dissociating may make us feel as if we have no emotions, it’s a lie. Our emotions are still very much present, straining on the lid of the box, ready to either explode when we least expect them or ooze out of us in ways we can’t control. In extreme cases where there has been a lot of trauma, dissociation can lead to:

gaps in our memories or inability to recall personal information (amnesia)

feeling detached from one’s own body and experience, as if you were observing yourself from the outside (depersonalization),

or experiencing the world and reality as if in a dream (derealization).

While at one end of the spectrum is zoning out, on the other is Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) where parts of us fragment into distinct identities and “take over” leading to loss of control and memory gaps. However, those are extreme cases.

Speaking to Our Dissociative Part

From an IFS perspective, dissociation is, at the milder levels, a manager, and at the more extreme levels a firefighter. Like our inner critic, little perfectionist, or rebel, our little dissociater is a younger version of us that early on tried to take on the adult role of protector. Terry Real calls it an “adaptive child”. To soothe our adaptive children, we need the “wise adult” in us to comfort them. In Internal Family Systems, this Wise Adult is called the Self or Self Energy.

Here’s how I spoke to my little dissociater:

Me: Hi there, Diss. I feel you. You’ve made it so I feel like I am underwater. Want to let me know why you put us in a submarine and submerged us?

D: Duh. Death. Another one. Someone needs to protect us from yet another tsunami of grief.

Me: I get it. It’s a lot. We are really, really sad. And also shocked. Once again, it was so sudden.

D: There’s never any time to prepare— it comes out of the blue. So, I come in and try to soften the blast. Just like with Dad. And J. and M. and J.

Me: I see that. Thank you so much for protecting me. Truly. I’m curious—what are you afraid is going to happen if you don’t do your job?

D: The wave will take us and we will drown. We won’t survive it.

Me: You’re afraid if we let ourselves feel the whole weight of the death, we won’t come back?

D: [nods head]

Me: Wow- that’s a big fear. I get it now. You’re afraid that we will also die.

D: No, that’s not quite it. I’m afraid that we won’t survive in a world where the people we love keep on being taken away.

Me: [my turn to nod head. And feeling a little teary-eyed, I won’t lie]. Yeah, I feel that. I am scared of that too… How about we be scared together?

D: [thinks about it for a minute]. Okay? How does that even look like?

Me: I think we’re doing it right now. Just staying with the fear. Look—we’re a little less underwater now. And we’re okay.

D: [surprised] Can you hold on to my hand for a little longer? Not quite ready to let go.

Me: As long as you need…

If I’m honest, I didn’t actually have this conversation with my dissociater until I actually wrote that down. And it did bring tears to my eyes because up until that moment, I didn’t realize that one of my biggest fears with death is not death itself but being abandoned.

I feel humbled now and grateful for this visceral reminder of how the work to know and understand oneself with compassion is an ongoing, lifelong practice.

Sigh.

Baby steps, people. Baby steps.